ITP Physical Computing

Home » Lab: Intro to Asynchronous Serial Communications

Lab: Intro to Asynchronous Serial Communications

Originally written on October 5, 2015 by Tom Igoe

Last modified on October 6, 2015 by Benedetta Piantella Simeonidis

Last modified on October 6, 2015 by Benedetta Piantella Simeonidis

Introduction

Contents [show]

From the first digital I/O and analog labs, you’ve been using asynchronous serial communication in order to send data back to the Arduino Serial Monitor. In this lab, you’ll get to know serial communication from a microcontroller to your personal computer a bit more in depth, so that you’re ready to start writing programs in other languages on your computer to interact with our microcontroller. You’ll send data from multiple sensors from Arduino to your computer and learn how to format the data, and to manage the exchange between the two.

What You’ll Need to Know

To get the most out of this Lab, you should be familiar with how to program an Arduino, and with the basics of serial communication. If you’re not, review the links below:

Things You’ll Need

| solderless breadboard | Arduino module | 22-AWG hookup wire |

| accelerometer (or two other analog sensors) | switch or pushbutton |

Connect the sensors

Connect two analog sensors to analog pins 0 and 1 like you did in the analog lab. Connect a switch to digital pin 2 like you did in the digital lab.

The photos and schematic in this lab show an accelerometer and a pushbutton. You don’t have to use these, though. Use whatever sensors are appropriate to your final application. While you’re figuring what sensors to use, use the most convenient sensors you’ve got in hand; perhaps two potentiometers for the analog sensors and a pushbutton?

(Diagram made with Fritzing)

Note: Not all accelerometers are the same. However, Analog Electronics makes a very popular series of accelerometers, the ADXL3xx series, that have three analog outputs for X, Y, and Z acceleration. This schematic should work interchangeably for most of them.

NOTE: only one program can control a serial port at a time. When you’re not using a given program, remember to close the serial port. You won’t be able to re-program the Arduino module if you don’t, because the serial terminal program will have control of the serial port.

Initializing Communication

What is asynchronous serial communication? Serial means that the two computers communicating are doing so one bit at a time, by sending pulses of data back and forth. Asynchronous means that the two computers that are communicating are each keeping track of time independently. There are three things the two computers need to agree upon:

- Electrical: what is the voltage of the pulses?

- Data rate: How often is a bit of data sent?

- Logic: Does low voltage mean the bit is a 0 or a 1?

Electrical and logic agreements are set for you when you use an Arduino. You set the data rate in your code. In your Arduino sketches so far, you’ve been setting the data rate to 9600 bits per second with this line:

Serial.begin(9600);

Whatever program you’re communicating to (whether it’s the Serial Monitor, CoolTerm, or another programming environment) has to set the same data rate. You can change both, as long as you change them to the same rate.

There are three connections between the two computers:

- a transmit line from sender to receiver

- a receive line from receiver to sender

- a common ground line

The transmit (sometimes called TX) and the receive (sometimes called RX) are relative: my transmit is connected to your receive, and vice versa. On the Arduino Uno, digital pins 0 and 1 are used for receive and transmit. They are attached to the USB-to-serial chip on the board. When you plug the Arduino into the computer, it shows up as a USB COM device, meaning a serial communications device. When you ask for a list of serial ports, whether in the Arduino Serial Monitoror CoolTerm, or any program, the Arduino will show up as a new port.

ASCII vs. Binary: What are you sending?

In order to communicate clearly between two devices, you need to understand the difference between ASCII and raw binary data.

To begin with, just send the value from one sensor, the first analog sensor (the first axis of the accelerometer in the photos) and divide the output to give a maximum value of 1023:

void setup() { // start serial port at 9600 bps: Serial.begin(9600);}void loop() { int analogValue = analogRead(A0); Serial.println(analogValue);} |

When you open the serial monitor, you should see a number between 0 and 1023 scrolling down the window. That’s because Serial.println() formats the value it prints as an ASCII-encoded decimal number, with a linefeed at a carriage return at the end. Also, the serial monitor assumes it should show you the ASCII character corresponding to each byte it receives.

The output from analogRead() can’t fit in a single byte, because the microcontroller’s analog-to-digital converter (ADC) reads the input with a resolution of 10 bits, or 210. To get the output into a single byte, map the output to a range from 0-255 like so:

void setup() { // start serial port at 9600 bps: Serial.begin(9600);}void loop() { int analogValue = analogRead(A0); int mappedValue = map(analogValue, 0, 1023, 0, 255); Serial.println(mappedValue);} |

Try it now, and your output should range from 0 to 255.

Try changing the Serial.println() to a Serial.write(). Now you get a range of garbage characters. What’s going on? The Serial.write()command doesn’t format the bytes as ASCII characters. It sends out the binary value of the sensor reading. Each sensor reading can range from 0 to 1023; in other words, it has a 10-bit range, since 210 = 1024 possible values. Since that’s more than the eight bits that can fit in a byte, you can either divide the value by 4 in the code above or use the map() function to get a range from 0 to 255, or 28 bits. For more background on this, see the notes on variables.

So, for example, if the sensor reading’s value is 234, then the Serial.write() command sends the binary value 11101010. If the reading is 255, then Serial.write() sends 11111111. If it’s 157, then the command sends 10011101. For more decimal-to-binary conversions, open your computer’s calculator and choose the Programmer view (press apple-3 on a mac, and Alt-3 on Windows). The garbage characters are characters corresponding to the ASCII values the Monitor is receiving. When the Serial Monitor receives a byte, it and assumes it should show you the ASCII character corresponding to that byte’s value.

For example, imagine that analogValue = 32:

- Serial.println(mappedValue) results in “32” with a linefeed and carriage return

- Serial.write(mappedValue) results in ” “, the space character, which has the ASCII value 32.

How many bytes does Serial.println(mappedValue) send when analogValue = 32?

Serial.println(mappedValue) actually sends FOUR bytes! It sent a byte to represent the 3, a byte to represent the 2, a byte to tell the Monitor to move the cursor down a line (newline), and a byte to move the cursor all the way to the left (carriage return). The raw binary values of those four bytes are 51 (ASCII for “3”), 50 (ASCII for “2”), 10 (ASCII for “newline”), and 13 (ASCII for “carriage return”). Check the ASCII table and you’ll see for yourself.

Send the data in many formats

Try this program and view the results in the Serial Monitor:

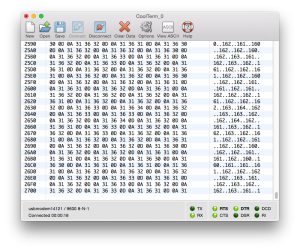

void setup() { // start serial port at 9600 bps: Serial.begin(9600);}void loop() { // read analog input, map it to make the range 0-255: int analogValue = analogRead(A0); int mappedValue = map(analogValue, 0, 1023, 0, 255); Serial.println(mappedValue); // print different formats: Serial.write(mappedValue); // Print the raw binary value Serial.print('\t'); // print a tab // print ASCII-encoded values: Serial.print(mappedValue, BIN); // print ASCII-encoded binary value Serial.print('\t'); // print a tab Serial.print(mappedValue); // print decimal value Serial.print('\t'); // print a tab Serial.print(mappedValue, HEX); // print hexadecimal value Serial.print('\t'); // print a tab Serial.print(mappedValue, OCT); // print octal value Serial.println(); // print linefeed and carriage return} |

You should get output like this:

â 11100010 226 E2 342 á 11100001 225 E1 341 á 11100001 225 E1 341 á 11100001 225 E1 341 à 11100000 224 E0 340 à 11100000 224 E0 340 ß 11011111 223 DF 337 ß 11011111 223 DF 337 ß 11011111 223 DF 337

This sketch is printing the raw binary value, then the ASCII-encoded binary value, then the ASCII-encoded decimal, hexadecimal, and octal values. You may never need all of these different formats, but you’ll likely need at least the decimal and the raw binary versions at some point.

Send the values for all three sensors

In the first example above, using Serial.write(), you sent one byte representing one sensor’s value, over and over. When you’re sending multiple sensor values, it gets a little more complicated. You need to a way to know which value represents which sensor. For example, imagine if you used the following loop to send your sensor values:

void loop() { for (int thisSensor = 0; thisSensor < 3; thisSensor++) { int sensorValue = analogRead(thisSensor); Serial.print(sensorValue); Serial.print(","); } } |

You’ll get a string like this:

452,345,416,234,534,417,325,452,231

How can you tell which value corresponds to which sensor? You don’t know which sensor is which. You could assume that if you start listening when the microcontroller starts sending that the first reading corresponds to the first sensor, but you can’t know that for sure. There are two ways to get your sensor values in order. You can use punctuation or you can use a call-and-response or handshaking method. Use whichever makes the most sense to you. They’re explained below.

Formatting Multiple Serial Data: Punctuation

One way to send the data such that it can be interpreted clearly is to punctuate each set of data uniquely. Just as a sentence ends with a period, you can end your data with a carriage return and a newline. Change the for loop above so that a carriage return and newline are printed at the end of each string of three values.

void loop() { for (int thisSensor = 0; thisSensor < 3; thisSensor++) { int sensorValue = analogRead(thisSensor); Serial.print(sensorValue); // if you're on the last sensor value, end with a println() // otherwise, print a comma if (thisSensor == 2) { Serial.println(); } else { Serial.print(","); } }} |

From this loop, you’d get output like this:

452,345,416 234,534,417 325,452,231

This is much better. Whenever you get a newline, you know that the next value is the first sensor.

Now write a program that reads the two analog sensors on your board and the one digital switch, and prints them out in this format:

analog1, analog2, switch analog1, analog2, switch analog1, analog2, switch

Start by setting up a constant for the switch pin’s number. Then in the setup, initialize serial communications at 9600bps, and declare the switch pin as an input.

const int switchPin = 2; // digital input void setup() { // configure the serial connection: Serial.begin(9600); // configure the digital input: pinMode(switchPin, INPUT); } |

In the main loop, use a local variable called sensorValue to read each input. Read the two analog inputs first, and print them with a comma after each one. Then read the digital input, and print it with a carriage return and linefeed at the end.

void loop() { // read the sensor: int sensorValue = analogRead(A0); // print the results: Serial.print(sensorValue); Serial.print(","); // read the sensor: sensorValue = analogRead(A1); // print the results: Serial.print(sensorValue); Serial.print(","); // read the sensor: sensorValue = digitalRead(switchPin); // print the results: Serial.println(sensorValue);} |

Once you’ve got a data format, all you have to do is to write a program that reads that format. You’ll see how do to that in these labs. Pick whichever is appropriate to the programming language you know:

- Two-Way (Duplex) Serial Communication Using An Arduino and Processing

- Two-Way (Duplex) Serial Communication Using An Arduino and P5.js

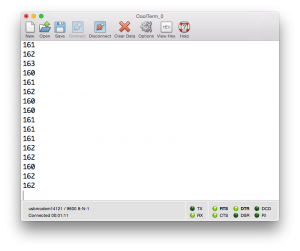

Flow Control: Call and Response (Handshaking)

Punctuation helps keep your data in order, but because asynchronous serial communication is asynchronous, you can run into a problem when the sender sends faster than the receiver can read. When this happens, the receiver program slows down as the serial buffer fills up. You can manage this by implementing some form of flow control. The simplest way do to this is using a call-and-response method, where the sending program only sends when it’s told to do so, and the receiving program has to request new data every time it finishes reading what it’s got.

You can add handshaking to the code above fairly simply. Modify the Arduino code as follows. First, add a a new block of code in the setup() This block sends out a message until it gets a byte of data from the remote computer:

void setup() { Serial.begin(9600); while (Serial.available() <= 0) { Serial.println("hello"); // send a starting message delay(300); // wait 1/3 second }} |

Now, modify the loop() by adding an if() statement to look for incoming serial data and read it.

void loop() { if (Serial.available() > 0) { // read the incoming byte: int inByte = Serial.read(); // read the sensor: sensorValue = analogRead(A0); // print the results: Serial.print(sensorValue); Serial.print(","); // read the sensor: sensorValue = analogRead(A1); // print the results: Serial.print(sensorValue); Serial.print(","); // read the sensor: sensorValue = digitalRead(switchPin); // print the results: Serial.println(sensorValue); }} |

The rest of the sketch remains the same. When you run this and open the serial monitor, you’ll see:

hello hello hello hello

Type any character in the output box and click Send. You’ll get a string of sensor values at the end of your hellos:

510,497,0

Type another character and click Send. It doesn’t matter what character you send, but the loop will always wait for an incoming byte before sending a new set of sensor values. When you write a program to receive this format, it just has to behave the same way you did:

Open the serial port Wait for a Hello Send a byte to request data Begin loop: Wait for one set of data Send a byte to request new data end loop

Advantages of Raw Binary vs. ASCII

All the examples shown here sent the sensor values as ASCII-encoded strings. As mentioned above, that means you sent three bytes to send a three-digit value. If that same value was less than 255, you could send it in one raw binary byte. So ASCII is definitely less efficient. However, it’s more readable for debugging purposes, and if the receiving program is well-suited to convert strings to numbers, then ASCII is a good way to go. For example, JavaScript sends data as ASCII strings almost by default, so it makes sense to use ASCII when writing in JavaScript. If the receiver’s not so good at converting strings to numbers (for example, it’s more challenging to read a multiple byte string in Arduino than in Processing) then you may want to send your data as binary values.

Advantages of Punctuation and Call-and-Response

The punctuation method for sending multiple serial values may seem simpler, but it has its limitations. You can’t easily use it to send binary values, because you need to have a byte with a unique value for the punctuation. In the example above, you’re using the value 10 (ASCII newline) as punctuation, so if you were sending your sensor values as raw bytes, you’d be in trouble when the sensor’s value is 10. The receiver would interpret the 10 as punctuation, not as a sensor value. In contrast, call-and-response can be used whether you’re sending data as raw binary values or as ASCII-encoded values.

Sometimes the receiver reads serial data slower than the sender sends it. For example, if you have a program that does a lot of graphic work, it may only read serial data every few milliseconds. For example, if you’re using P5.js, you may notice that using println() in the draw() loop will cause your sketch to slow down. The serial buffer will get full in that case, you’ll notice a lag in response time. This is when it’s good to switch to a call-and-response method.

沒有留言:

張貼留言